by Doug McCarty

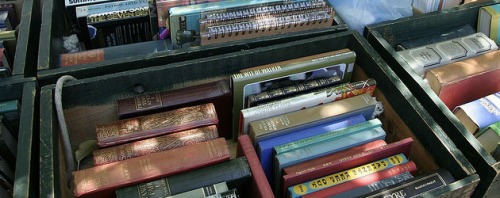

Garage Sale Books.

I remember when I was quite young, not quite eight years old, and I visited a neighborhood garage sale. I liked to read and was fairly precocious, so it was natural for me to be drawn to a box of old books in a corner, barely visible among all the various knickknacks and junk. Most of what was in the box was pretty uninteresting, the usual Reader’s Digest collections in hardback and the like. I did find something, though, that caught my eye—a tattered three-volume collection of Shakespeare’s works. I think I paid a dime for all three books.

William Shakespeare.

Now, what is a seven-year-old going to do with Shakespeare? Not that much, at first. The collection sat in the bookshelves in my room until a got a little older. Once I started, however, I read the entire set, all the plays, all the poems. I may not have understood everything I was reading all that well, but I kept on and on.

Certain plays held my attention more than others, Richard III especially. Any of you who have read the play or seen one or more of the numerous film adaptions know well the historical description of this king as a deformed hunchback with a withered arm who had his nephews (the sons of his late brother Edward IV) murdered in the Tower of London and who seized the crown through nefarious means. This description bothered me from the beginning, although I could never put my finger on why. Shakespeare, of course, could hardly write about the late king in a positive light, given that in 1591, when the play was probably written, the Tudor line that overthrew and killed Richard was still in charge in England. It always seemed strange that such an enigmatic figure was written in such a way, particularly when this character was given some of the finest lines read from among all the plays.

Sir Laurence Olivier as Richard III in 1955.

Years went by, and I reviewed the play from time to time, then very little after graduate school. In recent years, I discovered that there was a revival of interest in Richard, especially among those who wanted to reform the negative image created chiefly by Sir Thomas More and dramatized by Shakespeare. After a few moments of online research, I realized that I had been sleeping while new data and information on Richard was being uncovered. Unknown to me, there are several societies and research projects devoted to discovering the truth about Richard, who is, by the way, the current Queen of England’s 14th great-grand-uncle. There is a bunch of new stuff out there, but I will avoid boring anyone with all of it, even though it excites me.

Sir Ian McKellen as a historically-reimagined Richard III in 1995.

The most interesting thing I found out is that Richard III’s remains were discovered underneath a parking lot in 2012 after vanishing over five centuries ago, at the site of the medieval Greyfriars Church, where he was reputed to have been interred. The skeleton was identified, according to researchers, beyond a reasonable doubt as belonging to Richard.

This reasonably-positive identification was made through comparison of his mitochondrial DNA with that of two matrilineal descendants of Richard’s eldest sister, Anne of York. The spine showed considerable deformity consistent with scoliosis, which may have given Richard the appearance of having one shoulder higher than the other.

The Skeleton in the Grave.

The skeleton sustained at least ten wounds demonstrative of battlefield injuries of Richard’s day, when he was killed by the forces of Henry Tudor at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, which was the end of the Wars of the Roses and is typically considered to mark the end of the Middle Ages in England. There are plenty of gruesome details and conjectures about the events leading up to his death, and I invite you to do a web search for yourself, if you are at all inclined.

Portrait of Richard III

At this point, the team from the University of Leicester who participated in Richard III’s discovery, among other players, is planning to decode his genome, which has set off a flurry of controversy and protests, even involving Buckingham Palace.

Although history has been unkind to Richard, perhaps justly so in some instances, he was by many accounts an able and talented military commander, a king who reputedly enacted laws to protect the poor, and a noble who lived at the very least according to the principles of his time. He remains an enigma and perhaps always will, but that is what makes him so interesting, at least to me.