by Jay Parr

I am a devout agnostic. No, that is not an oxymoron.

After considerable searching, study, and introspection—and, having been raised in the Protestant Christian tradition, no small amount of internal conflict—I have come to rest in the belief that any entity we might reasonably call God would be so alien to our limited human perceptions as to be utterly, and irreconcilably, beyond human comprehension.

Gah. So convoluted. Even after something like a dozen revisions.

Let me try to strip that down. To wit: Humankind cannot understand God. We cannot remotely define God. We wouldn’t know God if it/he/she/they slapped us square in the face. In the end, we cannot say with any certainty that anything we might reasonably call God actually exists. Nor can we say with any certainty that something we might reasonably call God does not exist.

To horribly misquote some theologian (or philosopher?) I seem to remember encountering somewhere along the way, humankind can no more understand God than a grasshopper can understand number theory.

I mean, we can’t even wrap our puny little heads around the immensity of the known physical realm (or Creation, if you prefer) without creating incredibly simplistic, and only vaguely representative models.

Let’s look at some of the things we do know. With only a handful of notable exceptions the entirety of human history has happened on, or very near to, the fragile skin of a tiny drop of semi-molten slag just under 8,000 miles across. That’s just under 25,000 miles around, or a little more than two weeks’ driving at 70 mph, if you went non-stop without stopping for meals or potty breaks.

Even that tiny drop of slag can feel pretty vast to our little human perceptions, as anyone can tell you who has been on a highway in the American West and looked out at that little N-scale model train over there and realized that, no, it’s actually a full-sized freight train, with engines sixteen feet tall and seventy feet long and as heavy as five loaded-down tractor-trailers. And even though you can plainly see the entire length of that little train, it’s actually over a mile long, and creeping along at seventy-five miles per hour. Oh, and that mountain range just over there in the background? Yeah, it’s three hours away.

If we can’t comprehend the majesty of our own landscape, on this thin skin on this tiny droplet of molten slag we call home, how can we imagine the distance even to our own moon?

If you look at this image, in which the moon is depicted as a single pixel, it is 110 pixels to the earth (which itself is only three pixels wide, partially occupying nine pixels). At this scale it would be about eighty-five times the width of that image before you got to the Sun. If you’re bored, click on the image and it will take you to what the author only-half-jokingly calls “a tediously accurate scale model of the solar system,” where you can scroll through endless screens of nothing as you make your way from the Sun to Pluto.

Beyond the Moon, we’re best off talking about distances in terms of the speed of light—as in, how long it takes a ray of light to travel there, cruising along at about 186,000 miles per second, or 670 million miles per hour.

On the scale of our drop of molten—er, Earth—light travels pretty fast. A beam of light can travel around to the opposite side of the Earth in about a fifteenth of a second. That’s why we can call that toll-free customer-service number and suddenly find ourselves talking to some poor soul who’s working through the night somewhere in Indonesia—which, for the record, is about as close as you can get to the exact opposite point on the planet without hiring a more expensive employee down in Perth.

That capacity for real-time communication just starts to break down when you get to the Moon. At that distance a beam of light, or a radio transmission, takes a little more than a second (about 1.28 seconds, to be more accurate). So the net result is about a two-and-a-half-second lag round-trip. Enough to be noticeable, but it has rarely been a problem, as—in all of human history—only two dozen people have ever been that far away from the Earth (all of them white American men, by the way), and no one has been any further. By the way, that image of the Earthrise up there? That was taken with a very long lens, and then I cropped the image even more for this post, so it looks a lot closer than it really is.

Beyond the Moon, the distances get noticeable even at the speed of light, as the Sun is about four hundred times further away than the Moon. Going back up to that scale model in which the Earth is three pixels wide, if the Earth and Moon are about an inch and a half apart on your typical computer screen, the Sun would be about the size of a softball and fifty feet away (so for a handy visual, the Sun is a softball at the front of a semi trailer and the Earth is a grain of sand back by the doors). Traveling at 186,000 miles per second, light from the Sun makes the 93-million-mile trip to Earth in about eight minutes and twenty seconds.

Even with all that empty space, our three pixels against the fifty feet to the Sun, we’re still right next door. The same sunlight that reaches us in eight minutes takes four hours and ten minutes to reach Neptune, the outermost planet of our solar system since poor Pluto got demoted. If you’re still looking at that scale model, where we’re three pixels wide and the sun is a softball fifty feet away, that puts Neptune about a quarter of a mile away and the size of a small bead. And that’s still within our home solar system. Well within our solar system if you include all the smaller dwarf planets, asteroids, and rubble of the Kuiper Belt (including Pluto, which we now call a dwarf planet).

To get to our next stellar neighbor at this scale, we start out at Ocean Isle Beach, find the grain of sand that is Earth (and the grain of very fine sand an inch and a half away that is the Moon), drop that softball fifty feet away to represent the Sun, lay out a few more grains of sand and a few little beads between the Atlantic Ocean and the first dune to represent the rest of the major bodies in our solar system, and then we drive all the way across the United States, the entire length of I-40 and beyond, jogging down the I-15 (“the” because we’re on the west coast now) to pick up the I-10 through Los Angeles and over to the Pacific Ocean at Santa Monica, where we walk out to the end of the Santa Monica Pier and set down a golf ball to represent Proxima Centauri. And that’s just the star that’s right next door.

See what I’m getting at?

What’s even more mind-bending than the vast distances and vast emptiness of outer space, is that our universe is every bit as vast at the opposite end of the size spectrum. The screen you’re reading this on, the hand you’re scrolling with—even something as dense as a solid ingot of gold bullion—is something like 99.999999999% empty space (and that’s a conservative estimate). Take a glance at this comparison of our solar system against a gold atom, if both the Sun and the gold nucleus had a radius of one foot. You’ll see that the outermost electron in the gold atom would be more than twice the distance of Pluto.

And even though that nucleus looks kind of like a mulberry in this illustration, we now know that those protons and neutrons are, once again, something on the order of being their own solar systems compared to the quarks that constitute them. There’s enough wiggle room in there that at the density of a neutron star, our entire planet would be condensed to the size of a child’s marble. And for all we know, those quarks are made up of still tinier particles. We’re not even sure if they’re actually anything we would call solid matter or if they’re just some kind of highly-organized energy waves. In experiments, they kind of act like both.

This is not mysticism, folks. This is just physics.

The crux of all this is that, with our limited perception and our limited ability to comprehend vast scales, the universe is both orders of magnitude larger and orders of magnitude smaller than we can even begin to wrap our minds around. We live our lives at a very fixed scale, unable to even think about that which is much larger or much smaller than miles, feet, or fractions of an inch (say, within six or seven zeroes).

Those same limitations of scale apply in a very literal sense when we start talking about our perception of such things as the electromagnetic spectrum and the acoustic spectrum. Here’s an old chart of the electromagnetic spectrum from back in the mid-’40s. You can click on the image to expand it in a new tab.

If you look at about the two-thirds point on that spectrum you can see the narrow band that is visible light. We can see wavelengths from about 750 nanometers (400 terahertz) at the red end, to 380 nm (800 THz) at the blue end. In other words, the longest wavelength we can see is right at twice the length, or half the frequency, of the shortest wavelength we can see. If our hearing were so limited, we would only be able to hear one octave. Literally. One single octave.

We can feel some of the longer wavelengths as radiant heat, and some of the shorter wavelengths (or their aftereffects) as sunburn, but even all that is only three or four orders of magnitude—two or three zeroes—and if you look at that chart, you’ll see that it’s a logarithmic scale that spans twenty-seven orders of magnitude.

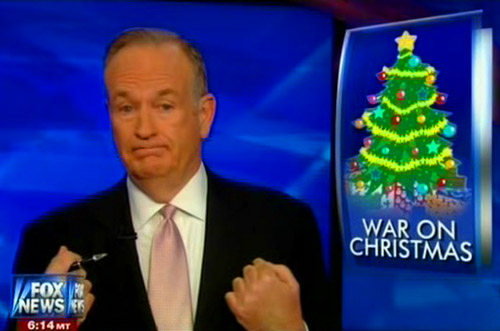

If we could see the longer wavelengths our car engines would glow and our brake rotors would glow and our bodies would glow, and trees and plants would glow blazing white in the sunlight. A little longer and all the radio towers would be bright lights from top to bottom, and the cell phone towers would have bright bars like fluorescent tubes at the tops of them, and there would be laser-bright satellites in the sky, and our cell phones would flicker and glow, and our computers, and our remotes, and our wireless ear buds, and all the ubiquitous little radios that are in almost everything anymore. It would look like some kind of surreal Christmas.

If we could see shorter wavelengths our clothing would be transparent, and our bodies would be translucent, and the night sky would look totally different. Shorter still and we could see bright quasi-stellar objects straight through the Earth. It would all be very disorienting.

Of course, the ability to perceive such a range of wavelengths would require different organs, once you got beyond the near-ultraviolet that some insects can see and the near-infrared that some snakes can see. And in the end, one might argue that our limited perception of the electromagnetic spectrum is just exactly what we’ve needed to survive this far.

I was going to do the same thing with the vastness of acoustic spectrum against the limitations of human hearing here, but I won’t get into it because acoustics is basically just a subset of fluid dynamics. What we hear as sound is things moving—pressure waves against our eardrums, to be precise—but similar theories can be applied from the gravitational interaction of galaxy clusters (on a time scale of eons) to the motion of molecules bumping into one another (on the order of microseconds), and you start getting into math that looks like this…

…and I’m an English major with a graduate degree in creative writing. That image could just as easily be a hoax, and I would be none the wiser. So let’s just leave it at this: There’s a whole lot we can’t hear, either.

We also know for a fact that time is not quite as linear as we would like to think. Einstein first theorized that space and time were related, and that movement through space would affect movement through time (though gravity also plays in there, just to complicate matters). We do just begin to see it on a practical level with our orbiting spacecraft. It’s not very big—the International Space Station will observe a differential of about one second over its decades-long lifespan—but our navigational satellites do have to adjust for it so your GPS doesn’t drive you to the wrong Starbucks.

Physicists theorize that time does much stranger things on the scale of the universe, and in some of the bizarre conditions that can be found. Time almost breaks down completely in a black hole, for instance. Stephen Hawking has posited (and other theoretical astrophysicists agree) that even if the expanding universe were to reverse course and start contracting, which has not been ruled out as a possibility, it would still be an expanding universe because at that point time would have also reversed itself. Or something like that; this is probably a hugely oversimplified layman’s reading of it. But still, to jump over to popular culture, specifically a television series floating somewhere between science fiction and fantasy, the Tenth Doctor probably said it best:

So far we’ve been talking about physical facts. When we get into how our brains process those facts, things become even more uncertain. We do know that of the information transmitted to our brains via the optic and auditory nerves, the vast majority of it is summarily thrown out without getting any cognitive attention at all. What our brains do process is, from the very beginning, distorted by filters and prejudices that we usually don’t even notice. It’s called conceptually-driven processing, and it has been a fundamental concept in both cognitive psychology and consumer-marketing research for decades (why yes, you should be afraid). Our perceptual set can heavily influence how we interpret what we see—and even what information we throw away to support our assumptions. I’m reminded of that old selective-attention test from a few years back:

There are other fun videos by the same folks on The Invisible Gorilla, but this is a pretty in-your-face example of how we can tune out things that our prejudices have deemed irrelevant, even if it’s a costume gorilla beating its chest right in the middle of the scene. As it turns out, we can only process a limited amount of sensory information in a given time (a small percentage of what’s coming in), so the very first thing our brains do is throw out most of it, before filling in the gaps with our own assumptions about how things should be.

As full of holes as our perception is, our memory process is even worse. We know that memory goes through several phases, from the most ephemeral, sensory memory, which is on the order of fractions of a second, to active memory, on the order of tens of seconds, to various iterations of long-term memory. At each stage, only a tiny portion of the information is selected and passed on to the next. And once something makes it through all those rounds of selection to make it into long-term memory, there is evidence in cognitive neuroscience that in order to retrieve those memories, we have to destroy them first. That’s right; the act of recalling a long-term memory back into active memory physically destroys it. That means that when you think about that dim memory from way back in your childhood (I’m lying on the living-room rug leafing through a volume of our off-brand encyclopedia while my mother works in the kitchen), you’re actually remembering the last time you remembered it. Because the last time you remembered it, you obliterated that memory in the process, and had to remember it all over again.

I’ve heard it said that if scientists ran the criminal-justice system, eyewitness testimony would be inadmissible in court. Given the things we know about perception and memory (especially in traumatic situations), that might not be such a bad idea.

Okay.

So far I have avoided the topic of religion itself. I’m about to change course, and I know that this is where I might write something that offends someone. So I want to start out with the disclaimer that what I’m writing here is only my opinion—only my experience—and I recognize that everyone’s religious journey is individual, unique, and deeply personal. I’m not here to convert anyone, and I’m not here to pooh-pooh anyone’s religious convictions. Neither am I here to be converted. I respect your right to believe what you believe and to practice your religion as you see fit…provided you respect my right to do the same. Having stated that…

Most of the world’s older religions started out as oral traditions. Long before being written down they had been handed down in storytelling, generation after generation after generation, mutating along the way, until what ends up inscribed in the sacred texts might be completely unrecognizable to the scribes’ great-great-grandparents. Written traditions are somewhat more stable, but until the advent of typography, every copy was still transcribed by hand, and subject to the interpretations, misinterpretations, and agendas of the scribes doing the copying.

Acts of translation are even worse. Translation is, by its very nature, an act of deciding what to privilege and what to sacrifice in the source text. I have experienced that process first-hand in my attempts to translate 14th-century English into 21st-century English. Same language, only 600 years later.

Every word is a decision: Do I try to preserve a particular nuance at the expense of the poetic meter of the phrase? Do I use two hundred words to convey the meaning that is packed into these twenty words? How do I explain this cultural reference that is meaningless to us, but would have been as familiar to the intended audience as we woulds find a Seinfeld reference? Can I go back to my translation ten years after the fact and change that word that seemed perfect at the time but that has since proven a nagging source of misinterpretation? Especially in the translation of sacred texts, where people will hang upon the interpretation of a single word, forgetting entirely that it’s just some translator’s best approximation. Wars have been fought over such things.

The Muslim world might have the best idea here, encouraging its faithful to learn and study their scriptures in Arabic rather than rely on hundreds of conflicting translations in different languages. Added bonus: You get a common language everyone can use.

But the thing is, even without the vagaries of translation, human language is—at best—a horribly imprecise tool. One person starts out with an idea in mind. That person approximates that idea as closely as they can manage, using the clumsy symbols that make up any given language—usually composing on the fly—and transmits that language to its intended recipient through some method, be it speech or writing or gestural sign language. The recipient listens to that sequence of sounds, or looks at that sequence of marks or gestures, and interprets them back into a series of symbolic ideas, assembling those ideas back together with the help of sundry contextual clues to approximate—hopefully—something resembling what the speaker had in mind.

It’s all fantastically imprecise—wristwatch repair with a sledgehammer—and when you add in the limitations of the listener’s perceptual set it’s obvious how a rhinoceros becomes a unicorn. I say “tree,” thinking of the huge oak in my neighbor’s back yard, but one reader pictures a spruce, another a dogwood, another a magnolia. My daughter points to the rosemary tree in our dining room, decorated with tinsel for the holidays. The mathematician who works in logic all day imagines data nodes arranged in a branching series of nonrecursive decisions. The genealogist sees a family history.

Humans are also infamously prone to hyperbole. Just ask your second cousin about that bass he had halfway in the boat last summer before it wriggled off the hook. They’re called fish stories for a reason. As an armchair scholar of medieval English literature, I can tell you that a lot of texts presented as history, with a straight face, bear reading with a healthy dose of skepticism. According to the 12th-century History of the Kings of Britain, that nation was founded when some guy named Brutus, who gets his authority by being the grandson of Aeneas (yeah, the one from Greek mythology), sailed up the Thames, defeated the handful of giants who were the sole inhabitants of the whole island, named the island after himself (i.e., Britain), and established the capital city he called New Troy, which would later be renamed London. Sounds legit.

In the beginning of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Gawain beheads the huge green man who has challenged him to a one-blow-for-one-blow duel, right there in front of the whole Arthurian court, but the man picks up his head, laughs at Gawain, hops back on his horse, and rides off. Granted, Gawain is presented as allegory rather than fact, but Beowulf is presented as fact, and he battles a monster underwater for hours, then kills a dragon when he’s in his seventies.

Heck, go back to ancient Greek literature and the humans and the gods routinely get into each other’s business, helping each other out, meddling in each other’s affairs, deceiving and coercing each other into to do things, getting caught up in petty jealousies, and launching wars out of spite or for personal gain. Sound familiar?

As for creation stories, there are almost as many of those as there are human civilizations. We have an entire three-credit course focused on creation stories, and even that only has space to address a small sampling of them.

Likewise, there are almost as many major religious texts as there are major civilizations. The Abrahamic traditions have their Bible and their Torah and their Qur’an and Hadith, and their various apocryphal texts, all of which are deemed sacrosanct and infallible by at least a portion of their adherents. The Buddhists have their Sutras. The Hindus have their Vedas, Upanishads, and Bhagavad Gita. The Shinto have their Kojiki. The Taoists have their Tao Te Ching. Dozens of other major world religions have their own texts, read and regarded as sacred by millions. The countless folk religions around the world have their countless oral traditions, some of which have been recorded and some of which have not.

Likewise, there are any number of religions that have arisen out of personality cults, sometimes following spiritual leaders of good faith, sometimes following con artists and charlatans. Sometimes those cults implode early. Sometimes they endure. Sometimes they become major world religions.

At certain levels of civilization, it is useful to have explanations for the unexplainable, symbolic interpretations of the natural world, narratives of origin and identity—even absolute codes of conduct. Religious traditions provide their adherents with comfort, moral guidance, a sense of belonging, and the foundations of strong communities.

However, religion has also been abused throughout much of recorded history, to justify keeping the wealthy and powerful in positions of wealth and power, to justify keeping major segments of society in positions of abject oppression, to justify vast wars, profitable to the most powerful and the least at risk, at the expense of the lives and livelihoods of countless less-powerful innocents.

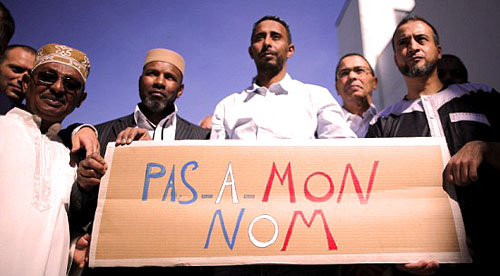

A lot of good has been done in the name of religion. So has a lot of evil. And before we start talking about Islamist violence, let us remember that millions have been slaughtered in the name of Christianity. Almost every religion has caused bloodshed in its history, and every major religion has caused major bloodshed at some point in its history. Even the Buddhists. And there’s almost always some element of we’re-right-and-you’re-wrong very close to the center of that bloodshed.

But what if we’re all wrong?

If we can’t begin to comprehend the vastness of the universe or the emptiness of what we consider solid, if we can only sense a tiny portion of what is going on around us (and through us), and if we don’t even know for sure what we have actually seen with our own eyes or heard with our own ears, how can we even pretend to have any handle on an intelligence that might have designed all this? How can we even pretend to comprehend an intelligence that might even be all of this? I mean seriously, is there any way for us to empirically rule out the possibility that our entire known universe is part of some greater intelligence too vast for us to begin to comprehend? That in effect we are, and our entire reality is, a minuscule part of God itself?

In short, the more convinced you are that you understand the true nature of anything we might reasonably call God, the more convinced I am that you are probably mistaken.

I’m reminded of the bumper sticker I’ve seen: “If you’re living like there’s no God, you’d better be right!” (usually with too many exclamation points). And the debate I had with a street evangelist in which he tried to convince me that it was safer to believe in Jesus if there is no Christian God, than to be a non-believer if he does exist. Nothing like the threat of hell to bring ’em to Jesus. But to me, that kind of thinking is somewhere between a con job and extortion. You’re either asking me to believe you because you’re telling me bad things will happen to me if I don’t believe you, which is circular logic, or you’re threatening me. Either way, I’m not buying. I don’t believe my immortal soul will be either rewarded or punished in the afterlife, because when it comes right down to it, even if something we might reasonably call God does exist, I still don’t think we will experience anything we would recognize as an afterlife. Or that we possess anything we would recognize as an immortal soul.

To answer the incredulous question of a shocked high-school classmate, yes, I do believe that when we die, we more or less just wink out of existence. And no, I’m not particularly worried about that. I don’t think any of us is aware of it when it happens.

But if there’s no recognizable afterlife, no Heaven or Hell, no divine judgment, what’s to keep us from abandoning all morality and doing as we please—killing, raping, looting, destroying property and lives with impunity, without fear of divine retribution? Well, if there is no afterlife, if, upon our deaths, we cease to exist as an individual, a consciousness, an immortal soul, or anything we would recognize as an entity—which, as I have established here, I believe is likely the case—then it logically follows that this life, this flicker of a few years between the development of consciousness in the womb and the disintegration of that consciousness at death, well, to put it bluntly, this is all we get. This life, and then we’re gone. There is no better life beyond. You can call it nihilism, but I think it’s quite the opposite.

Because if this one life here on Earth is all we get, ever, that means each life is unique, and finite, and precious, and irreplaceable, and in a very real sense, sacred. Belief in an idealized afterlife can be used—twisted, rather—to justify the killing of innocents. Kill ’em all and let God sort ’em out. The implication being that if the slaughtered were in fact good people, they’re now in a better place. But if there is no afterlife, no divine judgment, no eternal reward or punishment, then the slaughtered innocent are nothing more than that: Slaughtered. Wiped out. Obliterated. Robbed of their one chance at this beautiful, awesome, awful, and by turns astounding and terrifying experience we call life.

Likewise, if this one life is all we get and someone is deliberately maimed—whether physically or emotionally, with human atrocities inflicted upon them or those they love—they don’t get some blissful afterlife to compensate for it. They spend the rest of their existence missing that hand, or having been raped, or knowing that their parents or siblings or children were killed because they happened to have been born in a certain place, or raised with a certain set of religious traditions, or have a certain color of skin or speak a certain language.

In other words, if this one life is all we get? We had damned well better use it wisely. Because we only get this one chance to sow as much beauty, as much joy, as much nurturing, and peace, and friendliness, and harmony as possible. We only get this one chance to embrace the new ideas and the new experiences. We only get this one chance to welcome the stranger, and to see the world through their eyes, if only for a moment. We only get this one chance to feed that hungry person, or to give our old coat to that person who is cold, or to offer compassion and solace and aid to that person who has seen their home, family, livelihood, and community destroyed by some impersonal natural disaster or some human evil such as war.

If I’m living like there’s no (recognizable) God, I’d better be doing all I can manage to make this world a more beautiful place, a happier place, a more peaceful place, a better place. For everyone.

As for a God who would see someone living like that, or at least giving it their best shot, and then condemn them to eternal damnation because they failed to do something like accept Jesus Christ as their personal lord and savior? I’m sorry, but I cannot believe in a God like that. I might go so far as to say I flat-out refuse to believe in a God like that. I won’t go so far as to say that no God exists, because as I have said, I believe that we literally have no way of knowing, but I’m pretty sure any God that does exist isn’t that small-minded.

So anyway, happy holidays.

This is an examination of my own considered beliefs, and nothing more. I won’t try to convert you. I will thank you to extend me the same courtesy. You believe what you believe and I believe what I believe, and in all likelihood there is some point at which each of us believes the other is wrong. And that’s okay. If after reading this you find yourself compelled to pray for my salvation, I won’t be offended.

If you celebrate Christmas, I wish you a merry Christmas. If you celebrate the Solstice, I wish you a blessed Solstice. If you celebrate Hanukkah, I wish you (belatedly) a happy Hanukkah. If you celebrate Milad un Nabi, I wish you Eid Mubarak. If some sense of tradition and no small amount of marketing has led you to celebrate the celebratory season beyond any sense of religious conviction, you seem to be in good company. If you celebrate some parody of a holiday such as Giftmas, I wish you the love of family and friends, and some cool stuff to unwrap. If you celebrate Festivus, I wish you a productive airing of grievances. If you’re Dudeist, I abide. If you’re Pastafarian, I wish you noodly appendage and all that. If you don’t celebrate anything? We’re cool.

And if you’re still offended because I don’t happen to believe exactly the same thing you believe? Seriously? You need to get over it.